written by Dave Lieberth, Society board director

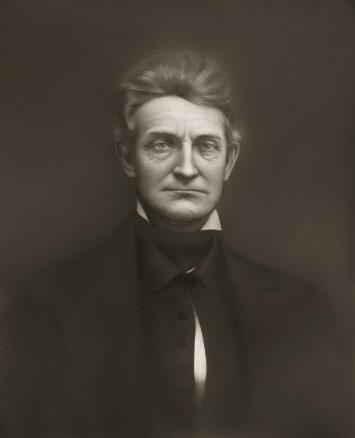

In 1844, Col. Simon Perkins was one of the wealthiest men on the Western Reserve. He farmed the 150 acres around the Stone Mansion, and raised cattle for milk and beef. But he knew that the rock-studded hillsides of his farm would better support flocks of sheep. Sheep production was becoming known as the nation’s first organized industry, with wool being the first international trade commodity. Ohio was a major producer of mutton and wool in the 19th century. (All of the soldiers in the Civil War wore wool uniforms.)

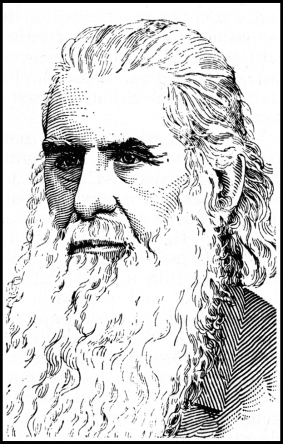

Col. Perkins wanted to raise a large flock of the finest sheep, and had heard of the reputation of John Brown – who had one of the area’s most developed talents for the breeding and raising of sheep, and the grading of wool. Brown had entered into a business venture as a sheep and wool merchant about 1839, a trade he had had an interest in since childhood. He brought with him to Akron some Saxony sheep that he bred with Perkins’ flock.

In 1844, Brown moved his family to the two room cottage (at Copley Road and Diagonal Road today,) describing it as “the best circumstances (his) family had ever known.” His agreement with Perkins gave him half of any profits of the enterprise, and half of any losses, with a payment to Perkins of rent for the cottage of $30 per year, which included a garden and fire wood.

Two of his sons were in jail in Akron for failure to pay their debts. Later, both Jason and Owen Brown would tend the Perkins flock, manage the gathering of wool according to their father’s direction and butcher meat for the use of both the Perkins and Brown families.

Prior to this time, American wool was generally regarded as inferior to that raised in Europe. Brown understood that many farmers were simply ignorant of what made their wool so poor: they routinely gathered all wool from all sheep in their flock, together with whatever mud, sticks, dirt and burrs stuck to it, and bundled it off to market.

There was a great price difference among different grades of wool. This was Brown’s specialty, and he developed a scale of nine wool grades, and as he gathered wool, would clean the wool to a degree previously unknown, then separate it by grades. Better and cleaner wool brought higher prices, and more profits for their owners.

By 1852, the Perkins-Brown flock of Merino and Saxony sheep numbered 1,300 head, and was regarded in national publications as one of the best herds in the United States, that is, their wool brought the highest prices. In 1853 the herd birthed 550 lambs and its wool brought an average of 80 cents per pound. The presence of this large herd prompted Akronites of the time to refer to the area around today’s Portage Path and Copley Road as “Mutton Hill.”

Col. Perkins built a woolen factory on Canal Street south of Cherry Street – a 3-story building, where each floor was devoted to different tasks of washing, sorting, spinning, dyeing and weaving. Nearly 60 people were employed in the operation, and eventually produced 500 yards of finished woolen product a day. (The factory closed in 1856 and became a flour mill.)

Brown spent much of the decade between 1844 and 1854 in Springfield, Massachusetts where he formed a depot for the storage of wool- not only for his products, but for other farmers as well. He also toured England, Germany, France and Luxembourg to identify new markets for their wool. For a few years, Perkins & Brown was a reasonably successful partnership. But John Brown was not a businessman at heart, and legal and financial problems began to mount.

Sadly, two of his children died during this period. Amelia was scalded to death in 1846 and Ellen died in 1849, both during times when Brown lived away from Akron. By 1854, the two men agreed amicably to part company, and the Brown family relocated to North Elba, New York.

Throughout this time, Brown remained an active abolitionist and a participant in the Underground Railroad. His business travels often took him over the Ohio River into Virginia (now West Virginia), and he regularly transported groups of runaway slaves, delivering them to stations in Ohio. Sometimes, when he sensed danger, he smuggled them all the way back to Akron and allowed them to hide in his home until other arrangements could be made. Although not a hotbed of activity, abolition was not a cause completely lost on Akron. It was home to anti-slavery sentiment, and its citizens contributed toward John Brown’s cause.

Spurred by his business failure and his sons’ advice, Brown made the decision to go to the Kansas Territory, where the future of slavery was being determined. On his way, he stopped at Akron, on August 13, 1854, where he collected funds, rifles, pistols, sabers and other weapons from the townspeople, including swords donated by Lucius Bierce. These swords went to Kansas with Brown, along with well-meant Akron support.